Miloš Pavlović

The dynamics of business competition in Serbia are such that there is an increasing gap between large corporations and small and medium-sized enterprises... A change in mindset towards collaboration and away from individualistic tendencies is needed...

Miloš Pavlović

Manager

"I may trust you with my life, but do I trust you with my money?" - a more moral version of a well-known quote from a U.S. military unit that can straightforwardly depict the foundations of business distrust. Initially, the quote is based on personal trust levels ("I may trust you with my life, but do I trust you with my wife?"), but now, we won't focus on male-female relationships and "the love of forbidden fruit."

I would focus on complete distrust in the relationships between competitors in specific industries. From lobbying races and fights over one or two percent market share, they need to see that they are losing, missing out on significant business opportunities, especially in an ecosystem where large players compete vertically in the value chain.

The current business structure of industries in Serbia is that 1% of companies generate 65% of total annual revenues. The rich are getting richer, and the poor are getting poorer (a factual projectile that hit us all directly from Davos); in our case, large companies are getting bigger while the SME segment swims in a sea of problems and tries to adapt to the market flexibly. This David and Goliath battle is most prevalent in the trade and manufacturing sectors, as both Davids and Goliaths generate the highest turnover in the Serbian industry. The fact that the big ones have started to "squeeze out" the small ones is evidenced by the data from the manufacturing sector, where the revenue jump of large companies increased 3.3 times from 2007 to 2022, while the revenue of the SME segment increased by nearly two times, with equal growth in the number of companies in both segments (CAGR 07/22: 4%-5%). In that same 2007, the share of large companies in the total turnover of the manufacturing sector was 60%, while today it is 75%. According to this data, it can be observed that two thousand large companies are entering the scene and taking on an increasingly important role in the country's economy. But what about the 209 thousand that make up our SME segment?

That the market will become more competitive for SMEs in Serbia is shown by the inflow based on foreign direct investments, which increased by 13% from 2014 to 2022 and amounted to 3.7 billion euros from January to October last year, an 8% increase compared to the same period the previous year. The most significant part of these foreign investments went to the construction and manufacturing sectors, where the most invested sectors are related to high technologies and medium-high technologies. Logically, the manufacturing sector has become a target for foreign investors - process, export, earn, and part of the profit through dividends, interest, and reinvested earnings (the outflow of reinvested earnings is always available to the owner and can be taken out of the country) paid through "the branch." On the other hand, initiating exports and developing the labor market traditionally represent some of the most significant benefits of foreign investments. Still, in the long run, low integration with the local economy means a substantial problem for private domestic companies in Serbia. Why low integration? Because 60% of the raw materials used by large companies are imported, we cannot break free from the trade deficit; instead, it increases (2014 deficit = $5.351 billion, 2022 deficit = $8.902 billion). Regarding the trade balance, only 30% of the SME segment is export-oriented, while the other 70% still depends on the local market.

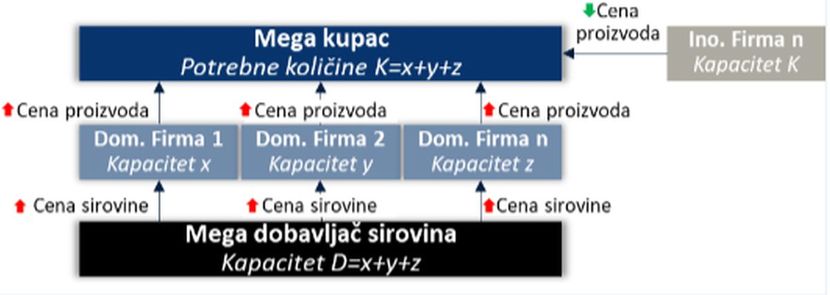

In the long run, this problem can be solved with a more systematic approach through policies and government measures. Regulating the activities of foreign investors to direct their interest in doing business in Serbia towards sectors where they would have greater integration can be one solution. However, to better explain what I see as a "quick-win" solution for the SME segment, I will try to explain with an example. I would take a specific example from the construction sector, specifically Expo 2027. All companies with small and significant connections with the value chain of that project are rubbing their hands and waiting for an excellent opportunity to compete and become suppliers. But does one of our domestic companies, whose primary activity is, for example, furniture or building material production, have the capacity to meet the demands of such a mega project? Maybe they do, but there are very few. That is why companies from Turkey, Poland, Italy, and companies of other origins compete for large local projects as contractors or suppliers of certain products and services with more competitive prices due to economies of scale, while our domestic SMEs have nothing left but to try to take a small piece according to internal capacities with prices that "kill" their margins and do not allow further growth (illustration 1).

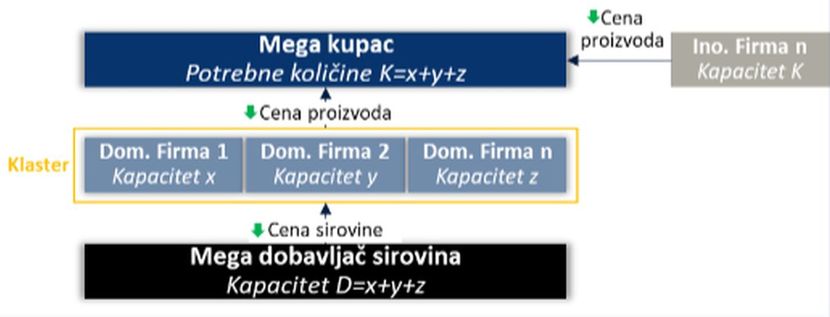

Put your ego aside and unite. United, you can achieve economies of scale and better negotiating positions with your raw material suppliers and domestic or foreign customers with a more competitive price and higher percentage margins.

Clusters can be formally formed in various ways. We have examples in Montenegro where UNIDO ("United Nations Industrial Development Organization") supports the Ministry of Economy in creating fisheries, viticulture, olive oil production, and various metal processing clusters to consolidate offerings and make companies more competitive. Besides Montenegro, there are numerous other countries where this practice is implemented so that clusters can be formed theoretically. However, based on field impressions, the initial problem differs from the procedures and forms of cluster creation. Still, distrust and pride convince a company owner that it is impossible to dismiss such an idea when resting their head in their hands. That's what needs to change.